An Expected-Value Framework for Fraud Decision-Making

Applying Machine Learning Concepts to Correctly Allocate Fraud Risk

Background

As Patrick McKenzie (and many others) have said, the optimal amount of fraud is non-zero.

What, then, is the optimal amount of fraud for a given business? And how can we measure the impact of the changes we make?

My first introduction to the fraud space was when I was leading an ML team responsible for fraud models. As I became more familiar with the field, I developed some intuition about how teams should think about measuring and optimizing their fraud prevention systems. Starting from ML frameworks gave me a set of tools for thinking about the problem that I’ve found both helpful and often under-appreciated.

My hope with this article (and hopefully an eventual series) is to help scale that knowledge and give you new tools and frameworks for thinking about how to optimize fraud systems and quantify their value.

Fraud Prevention as Binary Classifier

A binary classifier is an ML model that categorizes input data into one of two possible outcomes. In the case of risk systems at an e-commerce business: Fraud or Good Customer. This is almost always how ML models used to detect fraud are conceptualized and evaluated by the teams building them.

You can think of your entire fraud system as one big binary classifier. In reality, fraud prevention systems at large internet-based retailers are usually composed of a collection of binary classifiers. For example, a system might include:

A model that classifies transactions as risky,

Followed by an in-product experience like 3DS,

Ending with a manual review by a fraud investigator.

Each of these components effectively categorizes transactions as either fraudulent (by not allowing the user to transact) or legitimate (by allowing the purchase). This logic scales up to the entire fraud system: it categorizes transactions as fraudulent by blocking them, or as legitimate by letting them through.

Labels

We now have a system that labels transactions as fraudulent or not. But how do we know how well it’s performing?

When ML practitioners build classification systems, they refer to what the system predicts as the labels. In the fraud space (and other classification domains), an outcome of the type we’re trying to predict is called a positive.

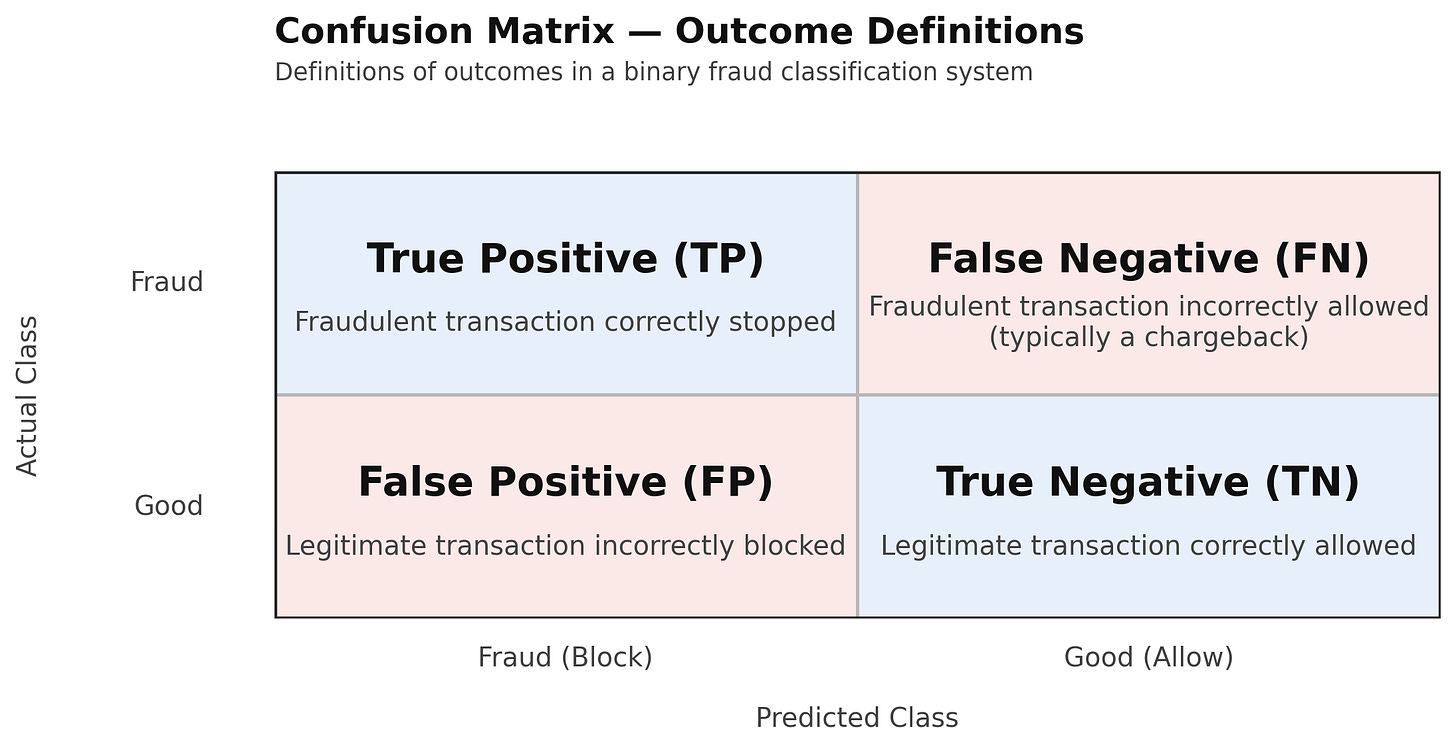

In this case, transactions our system predicts to be fraudulent are positive labels, and those it predicts to be good customers are negative labels. We also need to note whether the system got the predicted label correct. We do this by adding “True” or “False” depending on whether our detection system was right. This leads to four possible states for any transaction:

True Positive (TP)

False Positive (FP)

True Negative (TN)

False Negative (FN)

False labels—especially positives—can be tricky to grasp. A false positive is when the system incorrectly labels something as fraud. In practice, this is a good customer whose transaction was blocked due to fraud prevention activities (e.g., declined by a model, rejected by a reviewer, or abandoned during a 3DS step).

False negatives are easier to understand: they’re chargebacks. They occur when a transaction is allowed through but later results in financial loss.

True labels, in contrast, represent correct decisions:

True Positives: Fraudulent transactions correctly stopped.

True Negatives: Legitimate customers who successfully completed their transactions.

We can easily see when our system errs on negative labels (transactions we let through) because we observe chargebacks. But when we incorrectly label transactions as positive (by stopping them), it’s harder to know whether they were actually fraudsters or good customers. This is because we depend on the victims of fraud to initiate chargeback for source-of-truth labeling. When we stop a transaction due to suspected fraud, the victim of attempted fraud doesn’t have that opportunity to initiate a chargeback to confirm it was fraud, so we usually have no true signal.

Occasionally, the signal is clear (e.g., one of your investors is blocked by the system and calls your CEO), but most of the time these transactions live in a kind of Schrödinger’s Fraud Box — we can’t be certain whether they were fraudsters or legitimate users.

There will be a separate doc on how to estimate these values (hint: you need to run a holdout experiment). For the purposes of this exercise, let’s assume we can and do know them.

The Confusion Matrix

We now have our four potential states. To understand how a classification system performs, ML practitioners use a simple chart called the confusion matrix, which buckets transactions by the actual (y-axis) and predicted (x-axis) classes:

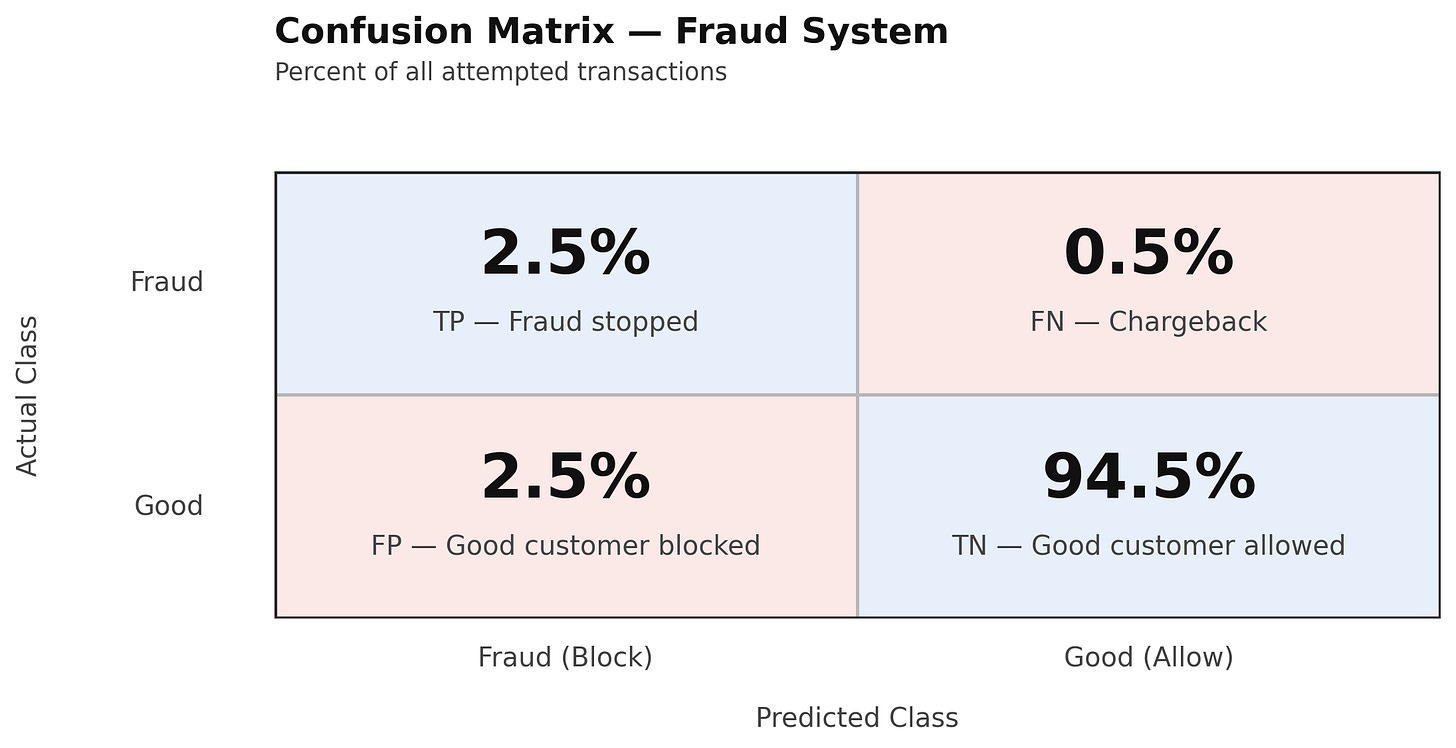

Typically, ML practitioners count the number of examples in each cell, but I find it easier to work in percentages.

Here’s an example confusion matrix for a hypothetical fraud system (numbers in this system have been chosen to be fairly representative of how systems I’ve seen actually perform):

In this system:

5% of attempted transactions are blocked (the total of the predicted-positive column).

That 5% is evenly split between good customers we blocked (2.5% False Positives) and fraudsters we stopped (2.5% True Positives).

The other 95% of transactions go through (predicted negatives). Of those, 0.5% are chargebacks (False Negatives) and 94.5% are legitimate (True Negatives).

If you were building a model to predict whether a picture is of a dog or not, you’d likely stop here and simply optimize for the lowest combined false-positive and false-negative rate. But we’re not categorizing pets — we’re stopping fraudsters — and we care about those errors differently.

The Cost of False Positives and Negatives

When your system correctly labels a transaction, there’s not much financial impact. You might pay a few cents to host models or for a manual review, but for simplicity, let’s assume those costs are negligible.

However, when the fraud detection system gets it wrong, there are real costs.

False Negatives (missed fraud): Typically equal to the chargeback cost — often larger than the average transaction size — plus processor fees and the labor cost of chargeback handling.

False Positives (blocked good customers): The intuitive starting point is the profit you’d have made from the transaction. But the true business cost is usually much higher. Blocked transactions are often larger than average, and since fraud is concentrated among new users, you may also lose much or all of the future lifetime value of that customer.

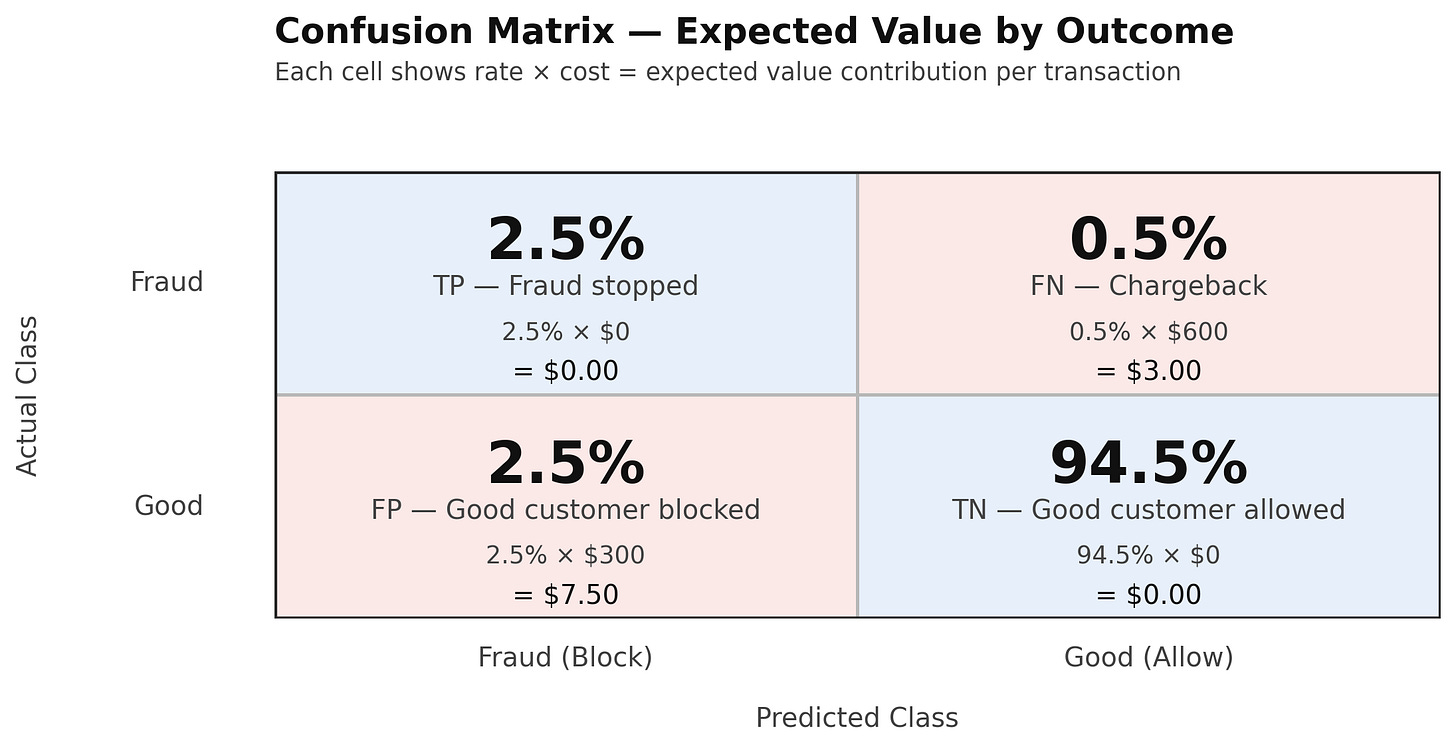

For this example, let’s assume:

Average chargeback size = $600

Average customer lifetime value = $300

An Expected Value Framework

We can now combine the confusion matrix with the costs we’ve defined to calculate the expected value (EV) — the average cost of fraud per transaction.

In economics, expected value represents the average outcome of an uncertain event. Mathematically:

where pi is the probability of an outcome and xi is its monetary value. In other words, expected value is the average cost per transaction once we weight each possible outcome by how often it occurs.

Therefore, by multiplying each cell’s probability by its cost and summing them, we can estimate the expected total cost of fraud in our system:

Sum up all of these numbers for a total value of $10.50 - the expected cost of the Fraud System inclusive of losses to the business of every transaction. That’s it!

Takeaways for Fraud Strategy

This framework reframes fraud prevention from optimizing model accuracy or minimizing losses into the explicit selection of decision thresholds that allocate economic risk.

While false negatives (missed fraud) are visible and painful, they are often not the primary economic driver of fraud loss. Across a wide range of assumptions, false positives — blocked legitimate customers — represent the majority of expected cost due to lost lifetime value and suppressed conversion.

In our example system:

Only 3% of transactions are errors

Yet those errors generate $10.50 in expected loss per transaction

Over 70% of that loss comes from customer friction, not chargebacks

The implication is clear:

Optimizing fraud systems requires minimizing economic loss, not maximizing fraud catch rate.

This expected-value framework allows teams to:

Compare fraud strategies using a single dollar-denominated metric

Quantify the ROI of model improvements, UX changes, or manual review

Make explicit tradeoffs between fraud loss and customer growth

In practice, the optimal fraud strategy is rarely the one that blocks the most fraud — it is the one that blocks the right amount of fraud.

Nice frame work overview on fraud strategy optimization

Fun thought exercise, Spencer. I'd suggest that there's an extra dimension you may consider which is "time" - there's a temporal difference between signal/feedback on a False-Positive (Customer Blocked) and a False-Negative (Chargeback). The former is often in real-time, whereas the latter is weeks, if not at least a month later. Opportunity often exists to tightly tie CS feedback to model optimization with the caveat that criminals are also incentivized to complain when their transactions are stopped. Models optimized on Chargebacks alone tend to suffer from "the horse has already bolted, won the race and been put out to stud when the stable door is closed". As someone who's been in the trenches, I know you've felt the frustration when Senior management yo-yo's between loosening models (due to complaints) only to tighten them up (when the chargebacks roll in).